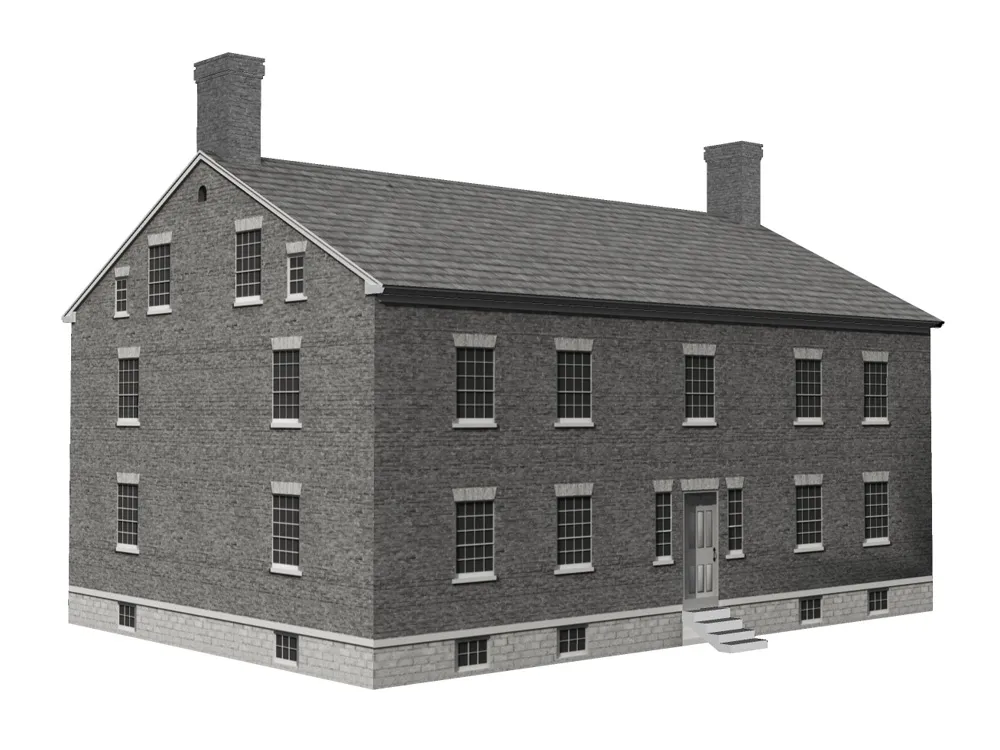

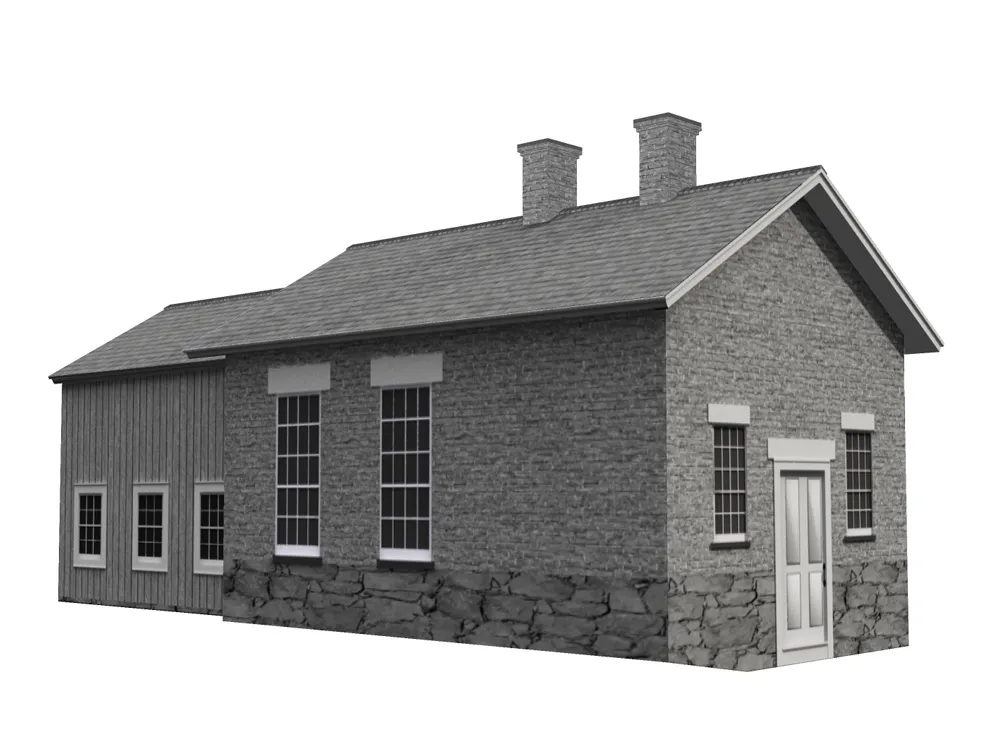

Brethren's Workshop

1822

A date stone set in the basement reads: This house built by Brewster and Allen, Master Masons, 1822

This structure is the oldest Shaker building remaining on the Church Family grounds. The building housed workshops for the men and boys of the community. As with many of the other buildings, the use of spaces changed over time with the shifts of industry and production. Rooms served as shops for a shoemaker, tailors, broom makers, and carpenters. Another room was set aside as a dentist office. Occasionally the upstairs rooms were used as bedrooms.

The Shakers were egalitarian, and the work that each Brother and Sister contributed to the community was equally valued.

While the tasks of daily life in a Shaker community were separated by gender, the work of Brethren and Sisters was often interdependent. For example, Sisters painted the furniture and wove the tape seats for chairs built by Brethren.

The Brethren fabricated looms and other tools used by Sisters in textile production, and built and equipped the Dwelling House kitchen so that the Sisters had an efficient place to produce meals for the community.

Shakers considered work to be a form of worship. Every act reflected an effort to seek perfection in daily living. The Shakers often improved manufacturing processes and designed better tools.

The Brethren’s Workshop may be the location where Brother George Price invented a tool for processing butter and a pea shelling machine. He pursued patents for both items.

In the late 1920s or early 1930s, Albany County rehabilitated the interior of the Brethren’s Workshop for healthcare services and updated the exterior in a Colonial Revival style with the addition of dormer windows and screened porches.

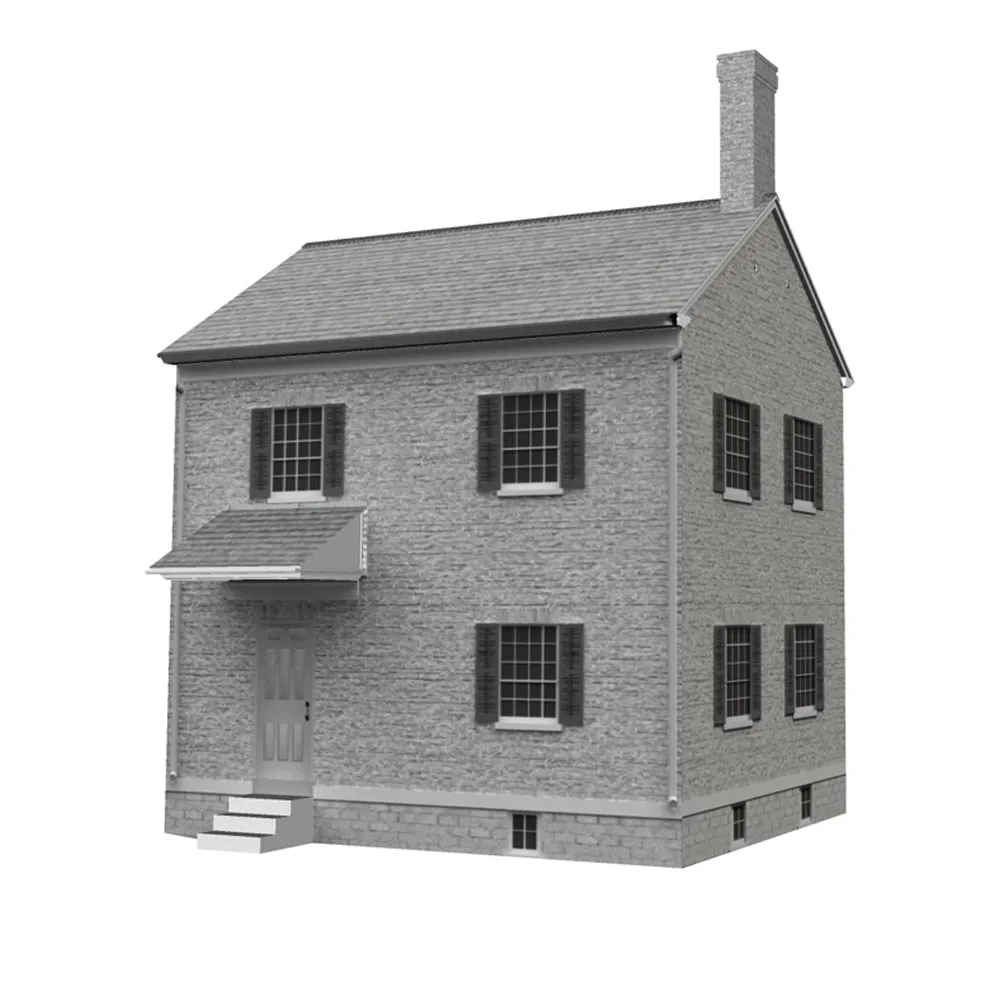

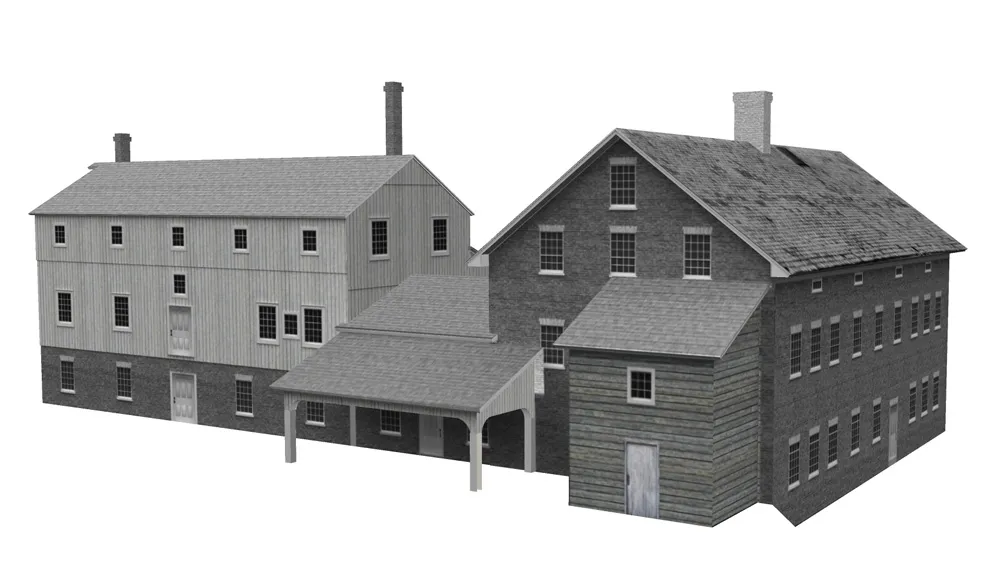

Ministry Workshop

1825

This building was designated for the use of the Mt. Lebanon Ministry Elders and Eldresses, and likely provided residential and work spaces

The rear wing of the building was added in 1852 to provide space for a furniture workshop. Journals record the Ministers’ frequent visits to and from various Shaker communities, and traffic was steady between Mt. Lebanon and Watervliet.

The Ministry usually came to Watervliet about 4 times a year, staying a total of 16-20 weeks. As representatives of the Central Ministry, Ministry Elders and Eldresses oversaw the integration of new Shakers at the South Family, helped other Families with various needs, mediated disagreements, and helped to allocate resources.

It was exhausting work, and even the most capable individuals sometimes requested to be relieved from duty.

In addition to their administrative responsibilities, Ministry Elders and Eldresses also worked as members of the community to aid the overall economy. The primary vocations of the Elders were shoemaking, tailoring, woodworking, and basketmaking. Elder Giles Avery was also a beekeeper.

Albany County added screened porches to the building during the 1930s, when it became the residence of the Commissioner of the Ann Lee Home. The building was later used for nurses’ quarters.

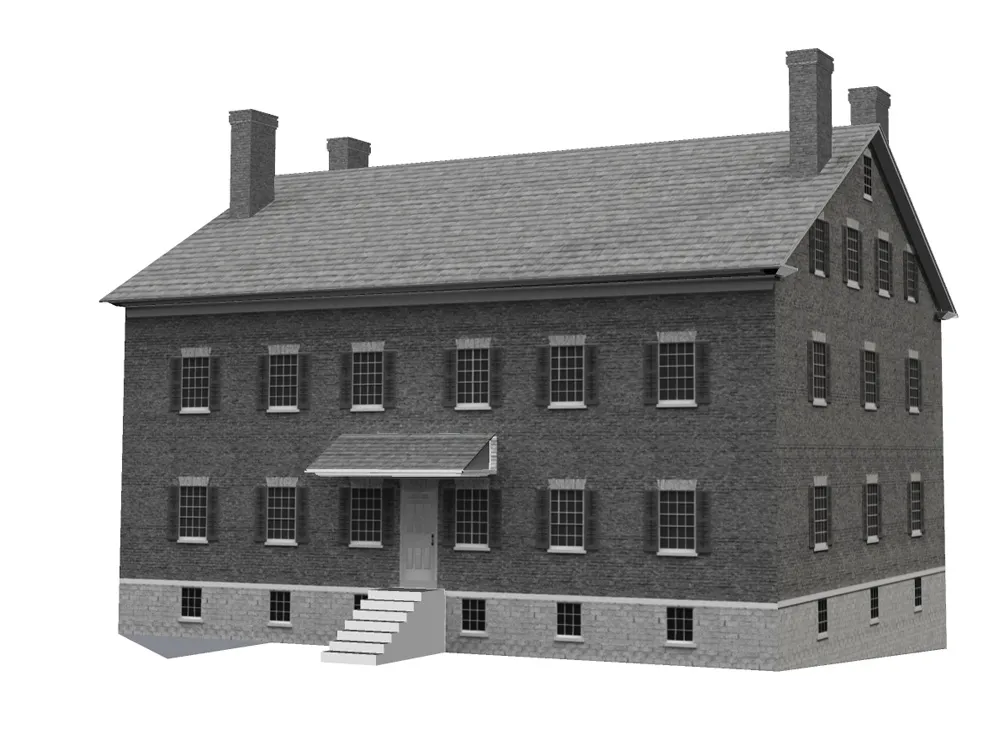

Trustees' Office

1830

With the exception of the raised benches in the Meeting House, the World’s People (as Shakers called non-Shakers) were generally not admitted on the grounds of the Shaker community

The remains of the “Great Gate” remind us that Shaker communities were intentionally separated physically from the World. However, it is important to remember that the Shakers were not isolated. In fact, their economy depended on commerce with the World.

The Trustees’ Office location outside the Great Gate is a clue to its function: the building served as the link between the Shaker community and the World. The Office housed the store, meeting rooms, a post office, and a dining room where guests were hosted.

The Shakers conducted business transactions here and hosted politicians, authors, social reformers, and civic leaders who came to meet the Shakers and learn about the distinct community.

Guests were often treated to high quality meals as part of the Shaker’s efforts to demonstrate the prosperity and quality of life in the community. There were rooms to accommodate visitors overnight.

Men and women shared responsibility at every level of the Shaker hierarchy. Shaker Elders appointed Brethren and Sisters as Trustees to manage the community’s business relationships and interact with visitors. The Trustees lived at the Office and ate meals here instead of at the Dwelling House with the rest of the community.

The Trustee’s Office was turned into a Preventorium when Albany County purchased the Church Family property in 1925. The facility was used to treat people who had been exposed to tuberculosis but who had not come down with the disease. The building was later used for a variety of health services for residents of the Ann Lee Home. Shaker Heritage Society used part of the building as an office when the organization was first established.

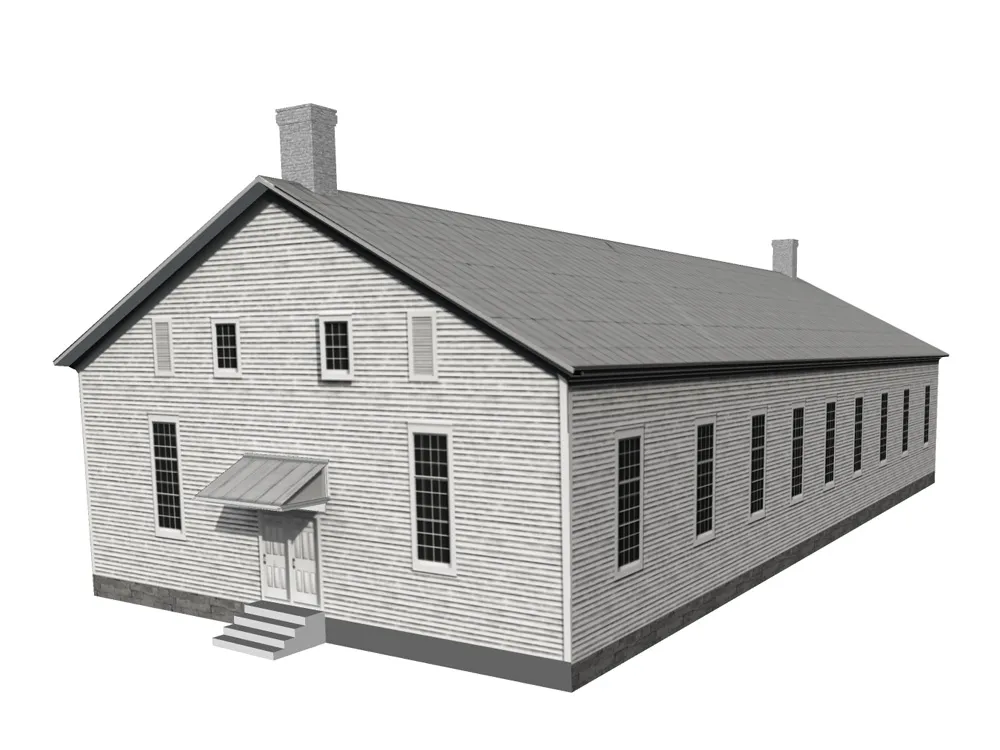

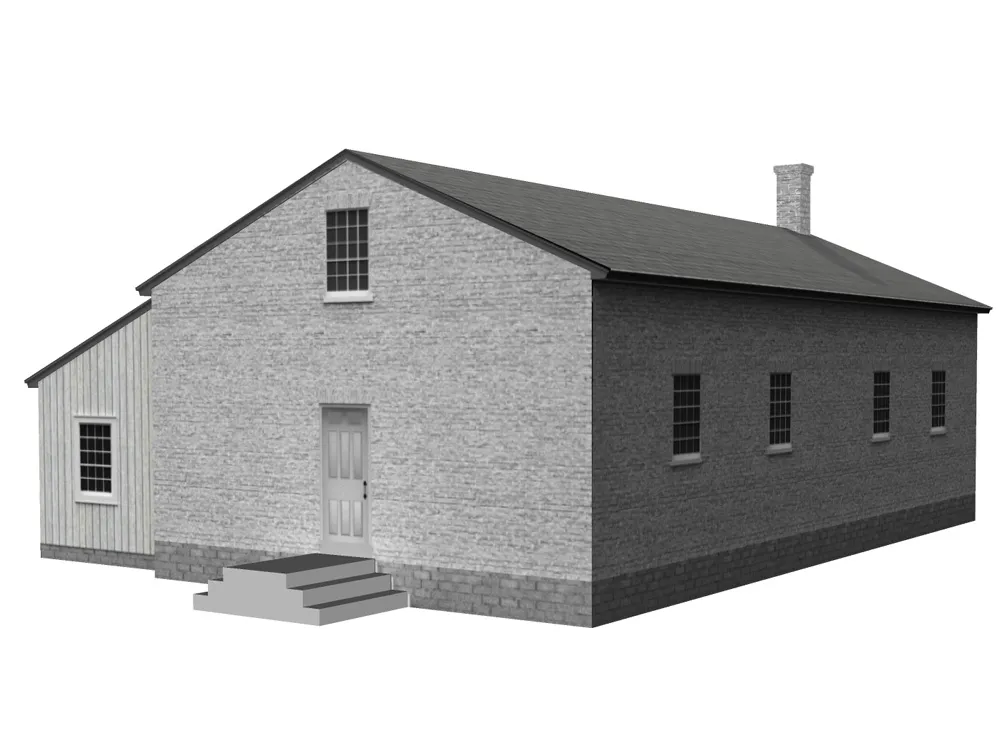

Meeting House

1848

Built as the third Meeting House at Watervliet, the 1848 Meeting House is the heart of America's first Shaker settlement

Shakers embraced song and dance as forms of spiritual expression. On Sundays the community gathered here to sing, dance, and pray for hours at a time. Shakers allowed visitors from the World at the services in order to build goodwill and attract new Believers.

Attending Shaker worship was a popular activity in the mid-1800s, and there are journal accounts of dozens or hundreds of carriages parked on the lane. Famous visitors included Herman Melville, James Fenimore Cooper, General Sherman, Governors Hamilton Fish, William Marcy, and Horatio Seymour, and many others. One Sabbath Day in August, 1849, Rufus Bishop noted “Many spectators--they filled all the stationary seats and several others.”

In 1845, the New Lebanon Ministry and the Watervliet Elders and Trustees met to discuss the construction of a new Meeting House. Not only had the Watervliet Shaker community grown too large for the 1791 Meeting House (which had replaced the original 1784 Meeting House), but there was also additional pressure from an increasing number of World’s People who visited the services.

Planning and design would take several years before construction began in 1848. Members of all four Watervliet Shaker Families were involved in the project, and Mt. Lebanon Brethren also assisted with the work. Brother Jesse Wells began working on the plans in 1846. Brother Freegift Wells notes in his journal that he worked on window sash for the building. Sisters helped with the construction also, plastering walls and painting. The building was officially dedicated during a celebration of Mother Ann’s birthday on March 1, 1849.

The symbolic purity of the building is expressed by both the white exterior and the simplicity of form. The floor plan is uniquely Shaker.

The central entrance at the north end was for the Elders, Eldresses, and Ministers; doors right and left of center were for the Brethren and Sisters who entered “shoe rooms” where they removed outerwear and changed into special shoes for worship before entering the Meeting Room. The large, two-story Meeting Room has a large floor for dancing and benches along the walls for Believers.

The expansive floor is made possible by an extensive truss system in the attic which supports the ceiling, omitting the need for columns. The tiered benches at the south end were built into the structure to accommodate the Worlds People. These visitors entered through the double doors on the south elevation and were required to sit separately, with men on one side and women on the other. The acoustics are ideal for carrying the sound of unaccompanied voices.

In 1837, a spiritual revival began at Watervliet as young girls at the South Family began to experience a series of visions and trances. Affected worshippers fell into a trance and “channeled” the spirits of ancestors, Shaker leaders, and other famous people. The experiences spread to other Shaker communities and lasted for a period of about 15 years known as the “Era of Manifestations” or “Mother Ann’s Work.”

Those who received the spiritual messages were known as “instruments,” and in some cases they documented the messages received in “Gift” or “Spirit Drawings.”

Brethren and Sisters created thousands of new songs, poems, and other writings during this period. Shaker communities were given spiritual names, and Watervliet was known as “Wisdom’s Valley.” The Era of Manifestations was a part of the larger “Second Great Awakening” that swept across the United States. This radical time fueled the growth of evangelical religious movements, the Abolition movement, and the emergent women’s rights movement.

Today the Meeting House is the most intact of all large Shaker Meeting Houses in the country. The building was used as a community center and movie theater during the early years of Albany County’s ownership. Later, the Meeting Room became a Catholic chapel for the residents of the Ann Lee Home. Pews and an altar were inserted, and a few of the perimeter benches were removed for the installation of radiators.

Drying House

1856

This building was used to dry the large quantities of apples and other fruit grown in Church Family orchards

Shaker journals frequently mention apple harvests followed by days of slicing and drying apples. Dried apples were packed into barrels and used for making applesauce and pies.

Shakers lived a seasonal lifestyle, structured around the cycle of planting, cultivating, and harvesting crops. Today, the orchard across Heritage Lane is the only remaining trace of extensive Shaker agriculture. At one time, the four Shaker Families owned or leased around 4,000 acres in the region.

The Shakers kept up to date with the modern farming practices. Food grown on their lands fed the Shaker community, and surplus was sold at farm side stands and public markets. Some crops were grown primarily or exclusively for sale to the public or were used for the seed and herbal medicine industries.

Albany Airport is now located where the Shakers once grew a variety of crops including acres of roses used to produce rose-water.

The Shakers frequently adapted buildings as needs changed, and the building was modified to serve as a henhouse in the early 1900s. Later, Albany County converted the building into a creamery for the Ann Lee Home, piping in water from Shaker Creek to cool dairy products.

Wash House & Cannery

1858

The building employed steam power to operate the laundry and canning operations

Laundry was a major undertaking in a community that housed up to 100 people. Shakers were practical, and eager to embrace new technologies that increased efficiency and quality. Shakers developed a number of inventions and improved the inventions of others.

The communities shared information about technological advances. Shakers at Mt. Lebanon and Canterbury, New Hampshire invented the first mechanized washing machine in the 1850s. In March, 1858, Sister Phebe Ann Buckingham notes “Elder Bro CC & Geo. Price go to Enfield, Ct. for 2-3 days to see about a steam engine to wash with.” "We are trying to find the best way of washing."

After investigating a number of options, the Church Family decided to purchase one of the new machines from the Canterbury Shakers. The construction was not complete until December, 1859, when Phebe Ann reported "The washing goes exceeding well, everything works as well as can be expected for first time."

Canning was a major industry for the Shakers. In journal entries of 1862, Sister Phoebe Ann records many days spent canning succotash, corn, beans, and tomatoes.

Canning produce would continue through the first quarter of the 20th century, with the South Family labeling 100 dozen cans of tomatoes and 75 dozen cans beans in one day. Over the course of two days in 1918, the small group at the South Family shipped five truckloads of tomatoes to New York City and sold 600 cases to two local grocers.

Other canned produce included beans, corn, peas, pears, peaches, carrots, applesauce, and beets. In addition to the Wash House and Cannery, the complex included an Extract House that was moved and attached to the Wash House for making catsup and sauces.

The Wash House continued to serve as the laundry building when Albany County was operating the new Ann Lee Home on the property, although the equipment had most certainly been updated by the 1920s. The Cannery was demolished in the late 1920s or early 1930s and was replaced with the one-story garage wing that remains along Meeting House road today.

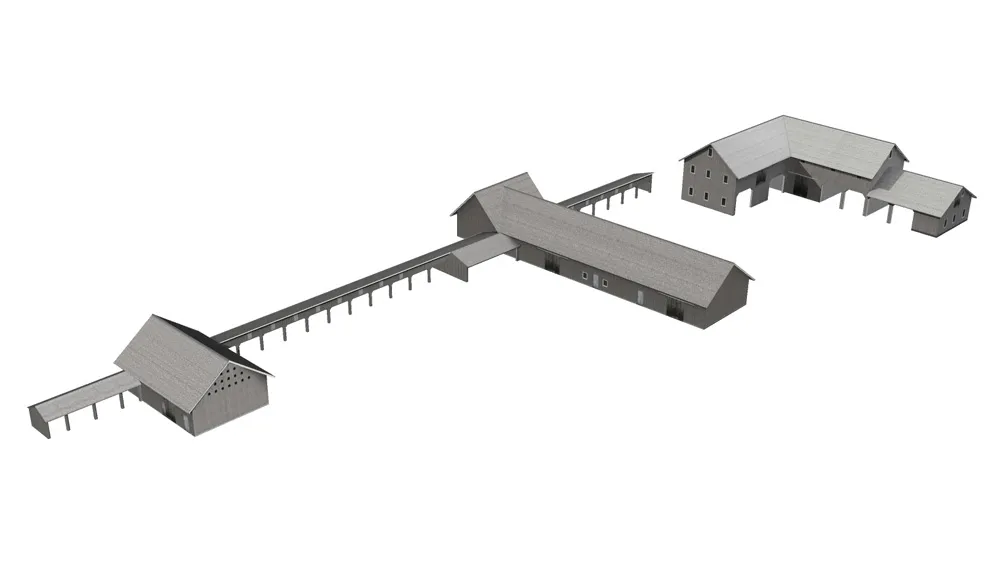

Barn Complex

1915

In 1914, the Church Family’s barn complex was destroyed by arson

With the hope that God would provide a future for them, the Shakers used insurance funds to rebuild the structures in 1915. As with many of the Shaker buildings, outside laborers were hired to help with the construction. Those who built the barn were supervised by the Church Family Elder, Josiah Barker.

The building is an exceptional example of an intact early 20th century barn complex. The largest section is the hay barn. This efficient and technologically advanced building is innovative in its use of roof ventilators and lightning rods to prevent catastrophic fires.

Large sliding doors built on opposite sides of the building allowed hay wagons to enter the barn on one side and exit the other side so that horses and wagons did not have to back out of the building.

Hay was unloaded and stacked through the building with the use of a large hay fork that was suspended from a track along the ceiling ridge.

The former cow barn is the central portion of the complex, and the small building at the east end is the manure shed. The overhead track between the cow barn and manure shed supported a bucket that transported manure from the barn to the shed. A banked ramp inside the manure shed allowed a wagon to backed into the shed so that the wagon bed would be level with the shed floor.

This configuration made it easier to shovel the composted manure into the wagon which was then used to spread the manure as fertilizer on surrounding fields.

While declining membership forced the Church Family to close in 1925, only ten years after the barn was built, the Hay Barn is now a setting for many community events and private functions.

Automobile Garage

1920

The garage was the last structure built for the Watervliet Shaker community

The building was built by George Dahm, whose biological sisters, Grace and Mary Dahm, were Shakers at the South Family. The garage was designed to store and protect the two Packard automobiles the Shakers owned.

Not only did the Shakers adopt new technology that saved time and energy, they believed in buying — and producing — high quality, durable items. Packards were considered to be vehicles that were a good value for the community.

Ann Lee Powerhouse

1927

When the Ann Lee Home was built, the schoolhouse was partially demolished and the building rebuilt to serve as the Powerhouse

The Church Family completed the community’s first two school buildings circa 1796 and 1823. In 1850, a new school house was built on what is now called Heritage Lane. It was a one-and-a-half story, gable-roofed, brick structure. In 1856 a small wood addition was built on the east elevation.

While the Shakers were celibate, there were a number of children in the community. Some children arrived with their families who joined the Shakers, others were indentured by widowed or impoverished parents hoping to ensure a stable future for their sons or daughters, and others were orphans who were taken in by the Shakers.

Young boys and girls lived separately under the care of Brethren and Sisters, and all children received an equal education. The school was accredited by New York State. Girls attended school in the summer, taught by a Sister, and a Brother taught boys in the winter.

This continued until the late-19th or early-20th century, when boys and girls attended classes together and a normal school year schedule was instituted. By the early 20th century, the school was part of the Watervliet District #14, and classes included both Shaker children and students from the World.

The building retained the walls, the main interior spaces and the location of the original entrance of the School House. It was designed to be fire resistant in design and Neo-Classical in appearance.