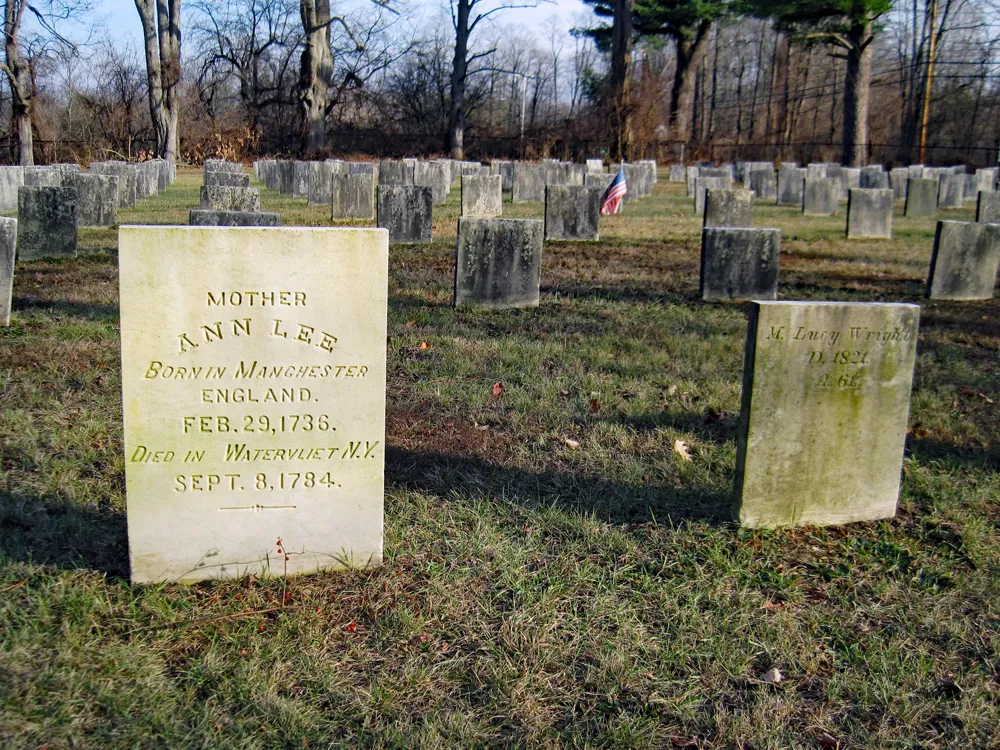

Mother Ann Lee

1736-1784

The illiterate daughter of a blacksmith, Ann Lee was born in Manchester, England in 1736

Ann Lee joined the Shakers in 1758. She married in 1762, but the marriage was an unhappy one. All four of her children died before reaching the age of six.

She was convinced that her suffering was a divine punishment for her sins. Ann experienced spiritual dreams and visions. Fellow Shakers began to call her “Mother Ann”, a leader of the congregation.

In 1774, a small band followed their charismatic leader to New York to seek a place to worship freely

The first years in Niskayuna were difficult. The group crowded into a small cabin. They suffered through several winters with little food. But, by 1779 they had established a small settlement.

Ann Lee led her followers in worship by dancing, singing, and speaking in tongues. Local people were perplexed and frightened and suspected Ann Lee was a witch or a British spy. Her supporters were also under suspicion.

This increased when the growing community refused to fight in the Revolutionary War. As a pacifist, Ann Lee attempted to dissuade others from taking up arms against the British. She soon was arrested and jailed, along with several other members of the small Shaker community.

Early on, Ann Lee’s followers began a practice of petitioning the State to support their cause. Due to their efforts on behalf of Ann, Governor George Clinton released her from jail. These events helped to publicize the Shakers and their new religion. Ann Lee's new notoriety prompted more visitors to travel to meet with her at Watervliet.

Mother Ann was inspired to begin preaching Shaker doctrine after the “Dark Day” on May 19, 1780. On this date, the sun went dark at midday across New England. This was possibly due to ash and smoke from a forest fire in faraway Ontario, Canada. The event came at a time of great religious and spiritual revival in New York and Massachusetts.

Many colonists feared that Judgment Day had arrived. In the wake of this event, the Shakers offered an attractive path to salvation for new converts.

The following year, Mother Ann began a missionary journey across the northeast. She attracted many new converts. She also encountered many people who violently disagreed with a woman preaching to the public and with the Shaker form of worship.

Once again, the Shakers were seen as threatening established congregations. They were physically attacked, jailed, and fined.

Despite the hardships, Mother Ann and her followers persevered for almost three years. They established new Shaker settlements in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine.

The travelers returned to Albany in spring of 1784. Ann Lee's brother Father William Lee died in July 1784, and Mother Ann died on September 8, 1784, at the age of 48.

Father Meacham

1742-1796

First American-born Shaker leader and successor of Mother Ann Lee

Joseph Meacham was the pastor of a New Light Baptist congregation in New Lebanon, New York. In 1780, he was one of the first people to travel to Watervliet to meet with Ann Lee. Meachum, his family, and many members of his congregation were early converts.

Mother Ann recognized Meacham’s skills. She declared that he would be her first “American-born son” and her successor.

James Whittaker (1751-1787), was a devoted follower of Ann Lee and an eloquent preacher. He led the Shakers for three years after her death.

Joseph Meacham assumed the leadership after Whittaker’s death in 1787. Meacham continued what Whittaker had begun and established the New Lebanon settlement as the Lead Ministry.

Located on the east side of the Hudson River, New Lebanon was closer than to the other Shaker communities in New England. It was also the location of Meacham’s own congregation.

The site was later renamed Mount Lebanon and became the administrative center of all Shaker communities

As successor to Mother Ann, Meacham established the complex system of communities that today we recognize as “Shaker.” The Shakers established a system of communal ownership of property and each community was economically separate. The effect was a new and controversial concept of "family." Men and women shared authority at each level of the hierarchy as Elders and Eldresses, Trustees, and Deacons and Deaconesses.

Crucially, Father Joseph appointed Lucy Wright as his female counterpart and co-equal as Lead Minister. Despite the Shakers’ professed belief in the equality of men and women, Meacham’s decision came as a surprise to many. Together, Father Joseph and Mother Lucy worked to establish the physical, social, and religious framework of the Shakers.

Upon Father Meacham's death in 1796, Mother Lucy took on an unusual role as the sole female head of a large religious organization.

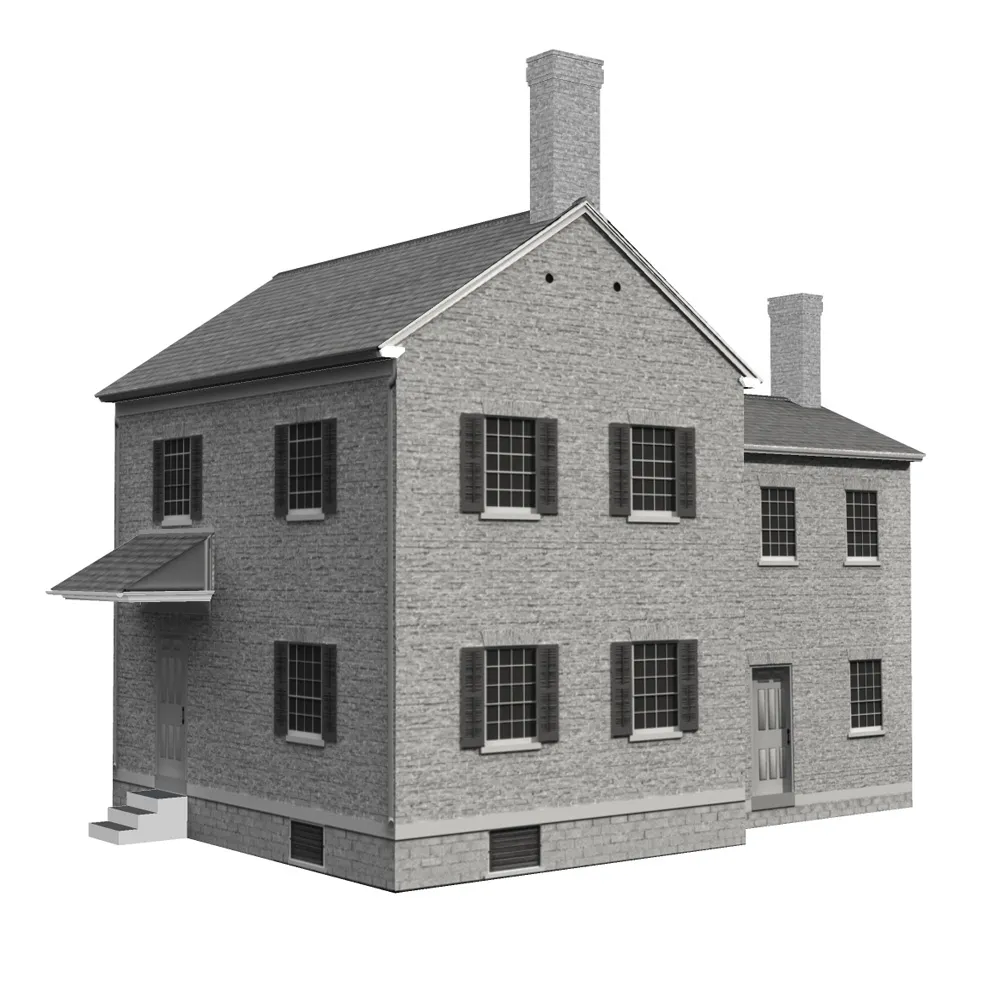

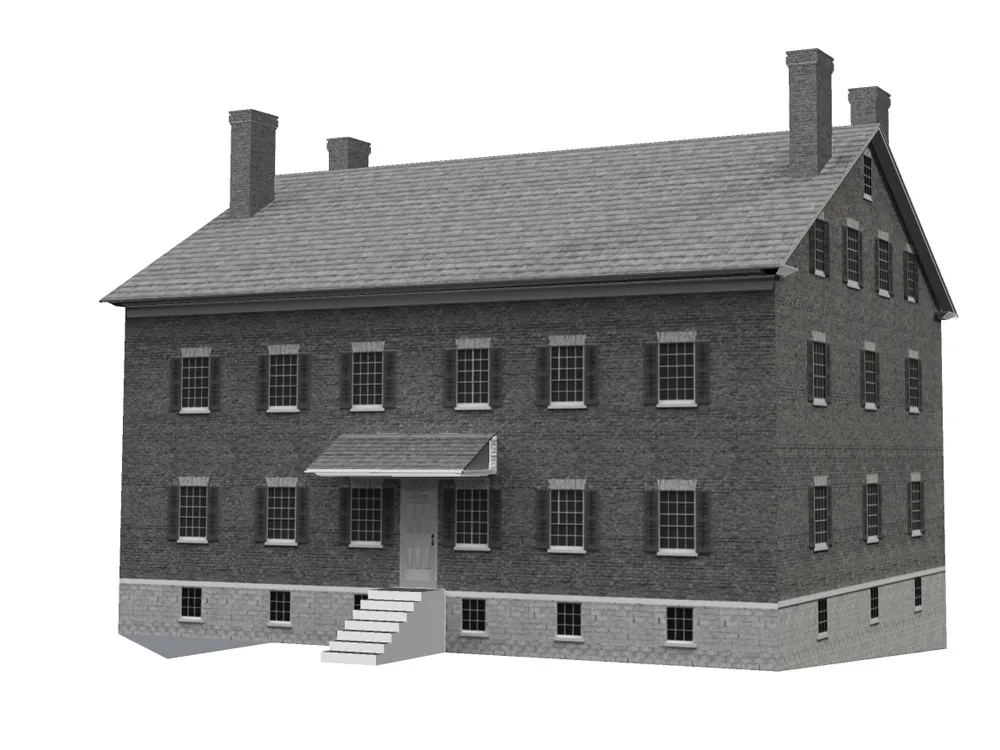

The Ministry’s House or Ministry Shop was built for Ministers from Mt. Lebanon who frequently visited the Watervliet community for weeks at a time.

While it was not built until after Father Joseph’s and Mother Lucy’s deaths, the Ministry is a reminder of the strong bond between the Watervliet and Mt. Lebanon communities that began during their early years as new members of the Shakers.

Mother Lucy

1760-1821

Lucy Wright worked to establish a uniform approach to daily life and to worship

Lucy and her husband Elizur Goodrich visited the Watervliet Shakers during the 1780s. They were a young, recently-married couple and both were intensely religious. Elizur joined the Shakers almost immediately. Many of his Goodrich relatives also joined. Lucy debated her own conversion for several months.

Mother Ann Lee recognized Lucy Wright’s natural gifts and sought to bring her into the fold at Watervliet

When Lucy did eventually join the Shakers, Elizur was no longer her husband but her spiritual brother. She resumed her maiden name of Wright and embraced her new identity as a Shaker sister. Mother Ann placed her in charge of the Sisters at Watervliet when she left on her missionary tour.

Father Joseph appointed Lucy Wright as co-equal Lead Minister. Upon Father Joseph’s death in 1796, Mother Lucy continued alone as the Lead Minister.

Twelve years after the death of Mother Ann, not all Shakers were willing to accept a woman as their leader. Several Brethren who opposed a “petticoat government” left the Shakers. Mother Lucy was remarkably effective as both an administrative and a spiritual leader. She and her supporters successfully deflected attacks on her leadership.

Mother Lucy saw the opportunity in the religious revivals taking place in the western frontier. She sent missionaries to establish Shaker communities in Kentucky, Ohio, and Indiana.

Under her leadership, the Shakers brought more order and union to everyday life. She established norms of dress, daily routines, interpersonal relations, and worship.

In the early 1800s, choreographed dances set to hymns began to replace the early individual and spontaneous forms of worship. Mother Lucy’s style of dance distinguished Shaker worship through most of the 19th century.

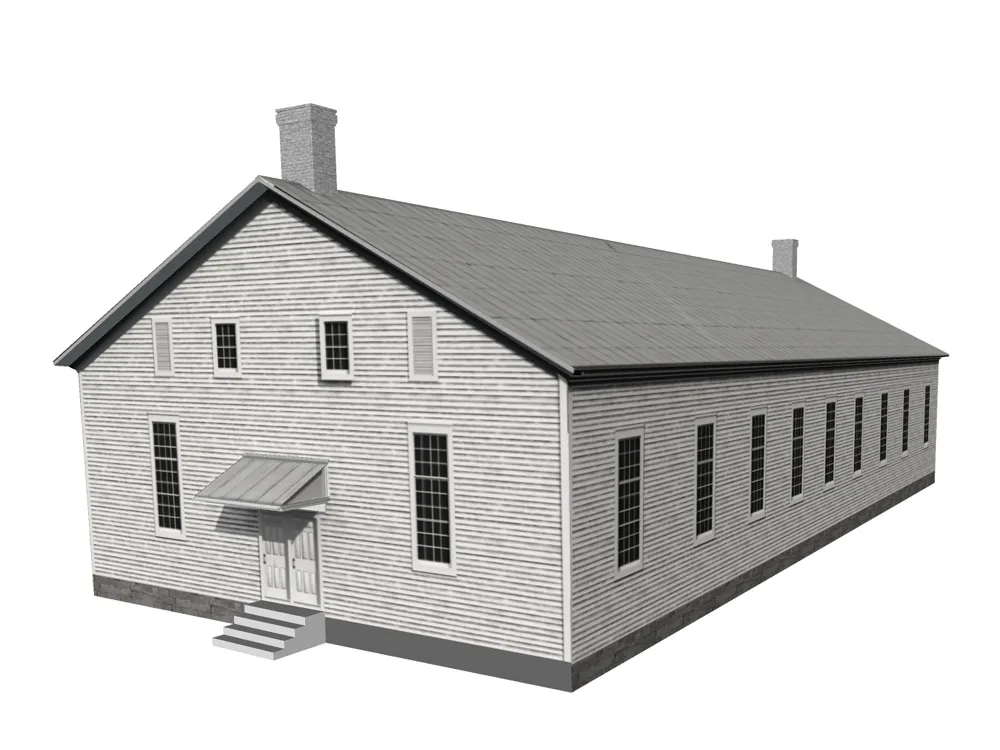

This ritual dancing attracted many visitors from the World. In 1848, the Shakers built a larger Meeting House to accommodate the growing numbers of visitors. This structure still remains at the Church Family site. The 1791 Meeting House was demolished in 1929.

Near the end of her life, Brother Freegift Wells of Watervliet urged Mother Lucy to publish the rules developed over her 25 years of leadership. It was only after her death in 1821 that these precepts were first published as The Millennial Laws. They were updated several times in the 19th century as the Shaker way of life changed.

Mother Lucy died during a visit to Watervliet and is buried in the Shaker cemetery next to Mother Ann Lee.

Brother David Miller

1775-1852

Brother David was a Shaker Family physician

He worked both in the herb industry and alongside other caregivers in the infirmary. He was among the Shakers who had known Mother Ann personally. As such, he was revered as a “first born” Believer.

The success of Shakers’ communities depended in part on sanitation and care for the sick. Brothers and Sisters were appointed as physicians in Shaker Families.

In the late 18th-century, American medicine combined Old-World folk traditions with Native American knowledge of local medicinal and culinary plants. Some of the medical caregivers had professional training or experience. Others learned through apprenticeship.

To treat severe injury or illness, the Shakers worked with trusted local physicians and surgeons.

Brother David sought plants for herbal remedies in the woods and fields of the Watervliet community. Later, these wild resources were augmented by herbs grown by the Shakers or purchased in bulk.

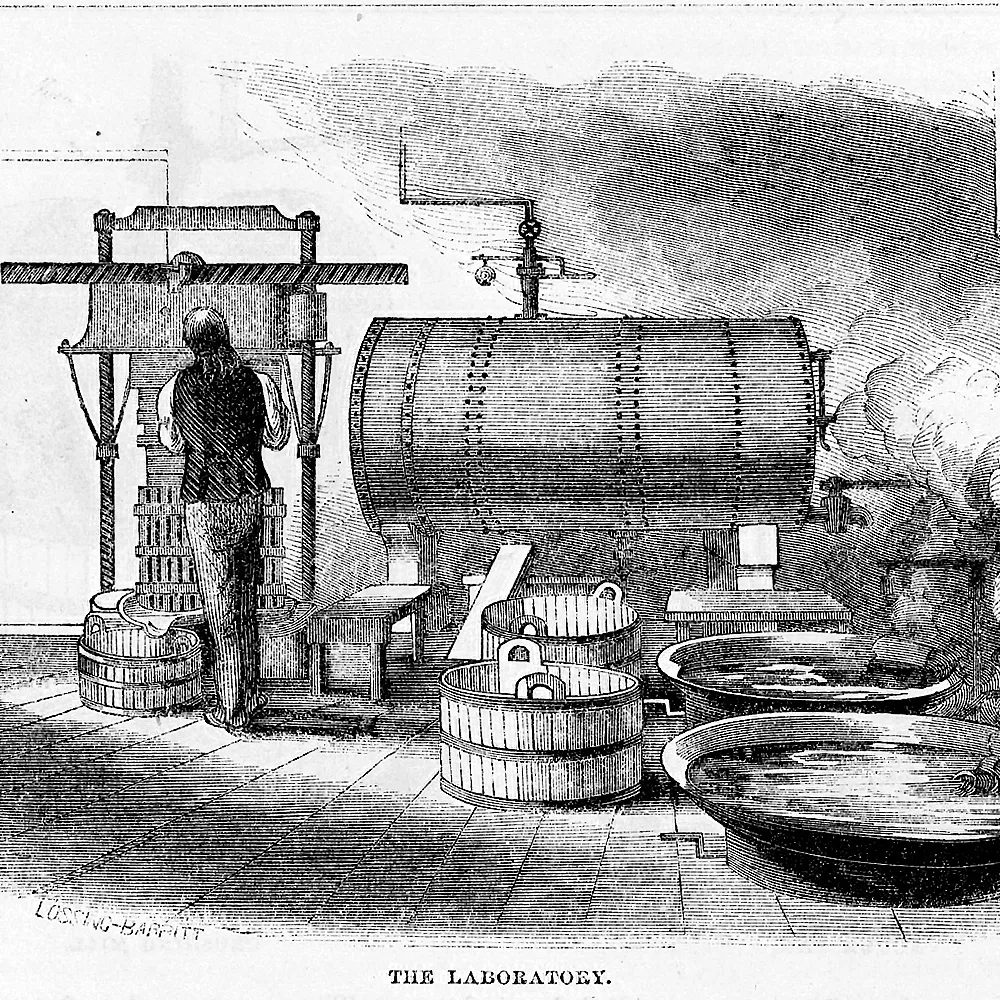

Beginning in the early 1800s, Shakers at Harvard and Mt. Lebanon began to sell surplus herbs to the World.

By 1820, the Shakers' production and sale of dried herbs and other products had grown.

Today, the American Pharmaceutical Association recognizes this as the first herbal medicine industry. The Shakers dedicated hundreds of acres to growing herbs. They produced dried and powdered herbs, elixirs, and pills for medicinal uses. Beginning in 1827, the Watervliet Shakers mass-marketed and sold their own pharmaceuticals. Their customers came from across the US and parts of Europe.

Shakers were known for their generosity and assisted non-Shaker neighbors in times of need.

One journal entry tells of a poor woman who arrived on foot through the snow. She sought medicine for her sick husband: “On her arrival she was cold, weary, and both her feet frozen. "She was kindly treated by those in the Office and taken home in a sleigh by Frederick and David [Miller], our physician.”

Brother Freegift Wells

1785-1871

Freegift Wells came to the Shakers as a young teenager with his parents and many siblings

His older brother, Seth Young Wells, converted most of the family in 1802.

Freegift became a carpenter, inventor, teacher, and religious leader. In 1824, he was one of eight brethren jailed for failing to pay a fine for refusing to serve in the military.

As pacifists, the Shakers sought relief from obligatory military service. Freegift traveled to Albany with Brother Calvin Green more than twenty times to make their appeal to the state Legislature . During the Civil War, the Shakers appealed to President Lincoln. He finally granted them conscientious objector status.

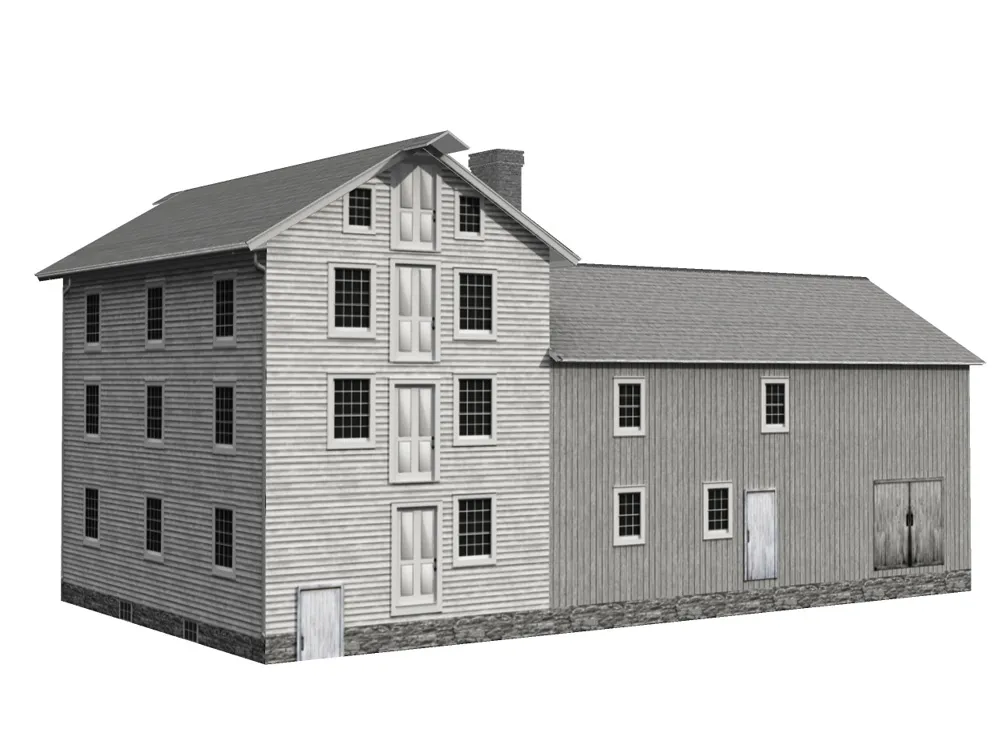

The Brethren’s Workshop was constructed in 1822 and was a hive of activity. Tailors, broom-makers, shoemakers, and even a dentist worked in various rooms. Brother Freegift spent many hours working here.

He kept a work journal beginning in 1812. This was the year the mill at Ann Lee Pond was built and ten years before the Workshop was constructed. The entries document his high level of production, the many tools he improved or invented, and the range of furniture and other items he made. He describes a threshing mill, steps for the dwelling house, a windmill for the West Family, chairs, and window sash for the 1848 Meeting House.

In 1820-21 he was the main person who conducted the silver pen business.

"When I made silver pens for sale, I kept an exact account of all stick which I used, even to files and sand paper. I also kept an exact account of the pens which I made and delivered for sale at the wholesale price and in one year I cleared $530... And I did this while serving as Elder Brother and with many jobs in joiner work..."

As members of an egalitarian society, Shakers usually did not sign their work. Freegift was one of the rare exceptions to this rule. Some of his furniture pieces are stamped with his initials.

His talents made Freegift very useful in other Shaker communities as well. The Church Elders sent Brother Freegift to Ohio in 1836. His mission was to help restore the governance and viability of the Shaker community at Union Village.

Skilled Shakers often traveled to other communities to share their talents. However, his overzealous nature caused friction in Ohio. He was called to return to Watervliet in 1843.

He was then appointed to be an Elder at the Church Family and continued in that position for 14 years, also occasionally teaching school.

Freegift worked with Mother Lucy Wright to record the laws that governed Shaker society, but he could not convince her to publish them. It was only after her death in 1821 that he finally succeeded in bringing the Millennial Laws of 1821 to print.

In April 1871, Phoebe Buckingham notes in her journal: “Freegift worked so hard outdoors in unseasonable heat that he is very sick and taken to infirmary. He does not realize it, it is thought to be his last sickness.” Freegift died that month at the age of 86, having been a faithful Believer for over 70 years.

Brother Nehemiah White

1811

Nehemiah White came to Watervliet as a child in 1830 along with several siblings and an aunt

During the Era of Manifestations, Nehemiah was one of a handful of young men who were “instruments”. Between 1842 and 1846, he channeled spirits and received messages and “gifts” to share with other Believers. Most of those receiving messages were young women. Nehemiah’s biological sister Nancy was also an active instrument. She received messages from many historical and spiritual figures. Nehemiah was also a talented singer, and one of the Shakers chosen to perform in Albany in 1870.

Perhaps Nehemiah’s own early years influenced his willingness to work with “his boys.” He knew what it was like to arrive in a very different setting as a child of seven.

There is no information on why Nehemiah White was sent to the Shakers. His parents and several other members of the family remained in the World.

A photograph taken around 1868 shows Nehemiah, one other man, and a group of boys. They are all dressed in identical pants and shirts and carefully posed on and around a wagon. The image is stereoscopic. When seen through a special viewer, the 2-part image appears three-dimensional.

Throughout his life, Brother Nehemiah remained in contact with relatives outside the community. The bond between biological family members remained strong. In 1862, the Church Family journals note that Nehemiah “took 3 barrels of apples, 2 bbls [barrels] potatoes and 1 bbl onions, carrots & beets to his relatives in Lansingburgh.”

Nehemiah’s father, Nehemiah White Sr. requested burial in the Shaker cemetery. While Nehemiah White, Sr. was not a Shaker, he wished to be close to family members who were Believers. The Shakers honored his request after his death in 1834. His is one of the graves of non-Shakers located along the first row in the cemetery.

Brother Nehemiah worked hard as a gardener. Like all Shakers he sought out new efficiencies in his work. In 1867, he “went to Mt. Lebanon to find out how they put up garden seeds. [He reported one] person there can put up 300 Ibs. in a day, while at Watervliet 2 persons put up only 100 Ibs. in a day.” He worked with Elder Giles Avery on beekeeping. They brought over 50 swarms out of a cellar after the winter to set them outdoors.

Shaker Brothers were eligible for the draft during the Civil War. Brother Nehemiah traveled to Albany several times to seek exemption from service.

In 1874 he was again appointed to serve as a Deacon. He helped to manage the business affairs and daily administration of the Church Family. When he died in 1887, Brother Nehemiah’s obituary in the Shaker Manifesto observed that he "toiled unselfishly for the gospel cause."

Mother Rebecca Jackson

1795-1871

Rebecca Cox Jackson was born in 1795 into a family of free African Americans in Philadelphia

Jackson experienced a spiritual conversion during a terrifying thunderstorm in 1830. A desire to preach took her far beyond Philadelphia.

Like Mother Ann Lee, Rebecca Jackson experienced dreams and visions. She predicted the future and healed others through prayer. She practiced what she called her “gift of power”: an ability to overcome periods of illness when she felt called to do God’s work. Unlike Mother Ann, Jackson taught herself to read and write. She kept a series of journals that document almost 30 years of her spiritual life.

While preaching in Albany in 1836, she went with a group to observe a Shaker meeting in the 1791 Meeting House. She was inspired by what she witnessed.

She visited the Shakers again in 1843 and wrote, “. . .for the first time in all my life, I have found a people to my sense that I believe to be the true people of God on earth.” (Humez, p. 171)

In June 1847 Rebecca Jackson and a disciple, Rebecca Perot arrived to live with the Watervliet Shakers. Jackson quickly became one of the noted participants during the Shaker meetings. She garnered respect and praise from the Watervliet Shakers. Still, she was restless and longed to resume her own mission work.

She and Perot returned to Philadelphia and remained for almost six years before returning to Watervliet in September of 1857. Rebecca Jackson finally embraced Shaker authority.

At her request, Eldress Paulina Bates granted permission for her to establish a small “Out Family” of the Watervliet Shakers in Philadelphia in late 1858

Jackson’s charisma and spiritual powers united a group of followers who lived as Shakers in Philadelphia with the World at their front door. She died in 1871 and was buried in Lebanon, Pennsylvania near relatives.

Rebecca Perot assumed the leadership of the Philadelphia family. She changed her name to Mother Rebecca Jackson in honor of her friend and mentor. This leads to some confusion as her photo is often incorrectly used to represent Rebecca Cox Jackson.

University of Massachusetts Press, 1981.

Rebecca Cox Jackson’s writings are published in the book "Gifts of Power: The Writings of Rebecca Jackson, Black Visionary, Shaker Eldress" edited with an introduction by Jean Humez.

Sister Samantha Bowie

1839-1892

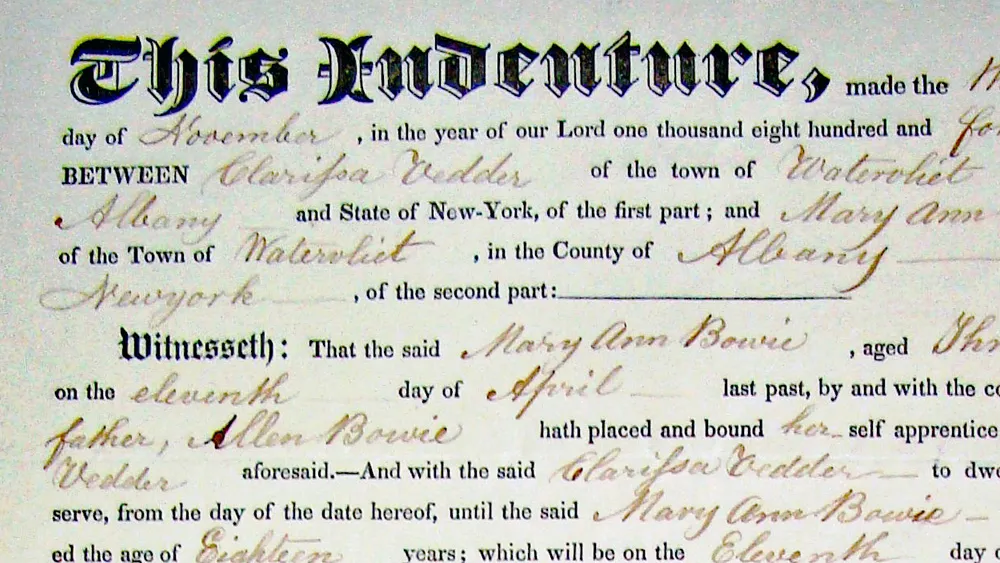

Samantha Bowie (nee Mary Ann) was brought to the Shakers at the age of three by her father, Allen Bowie, in 1842

The Shakers constantly sought converts from the World to build and maintain their communities. In some cases, entire families joined the Shakers. In others, an indenture was arranged for a child by a parent or guardian. A craftsperson agreed to train a child in a particular skill while providing room and board.

Many guardians simply sought a guarantee of shelter and education for a child. The Shakers saw the opportunity to train a new member of the community. On behalf of the Shakers, Sister Clarissa promised to provide Samantha “with meat, drink, washing, lodging and suitable apparel, and other things necessary”. She would also teach Samantha “the occupation of domestic economy” as well as reading, writing, and arithmetic.

For her part, Samantha was to “well and faithfully serve her said guardian, and obey all her lawful commands; and shall in all respects conduct her self [sic] in a faithful, honest and moral manner, and as a good and faithful apprentice.”

Upon her 18th birthday she was freed from this contract. Many apprentices left upon the end of the indenture. Some, like Samantha Bowie, remained and signed the covenant to join the community as a true Shaker.

Sister Samantha became a vital part of the Church Family. By 1860, she was living at the Trustees’ Office, an honor reserved for the most devout and devoted Shakers. She was apparently a good cook, since she was frequently assigned to work in the Trustees kitchen. Through the 1870s, she served meals to visitors. The bounty of the Shaker table advertised the success of the community.

The Shakers’ custom was to rotate Sisters and Brethren among various work assignments. In addition to her cooking duties, the journals note her activities:

17 Dec 1868: She went to the North Family to learn about making straw bonnets and then began doing so.

23 Jun 1870: Went to Ministry Shop to learn to make baskets of poplar chip from Eldress Ann Buckingham.

12 Dec 1870: Samantha is stitching some leather gaiters, "a new kind for us."

15 Dec 1870: Samantha working on small needle books.

16 May 1876: Set a hen on some duck eggs. Eggs hatched 12 June.

Samantha Bowie was one of the Shakers who traveled to New York City in July 1869. Like Nehemiah White, she was also one of a group of singers performing in Albany in October of 1870.

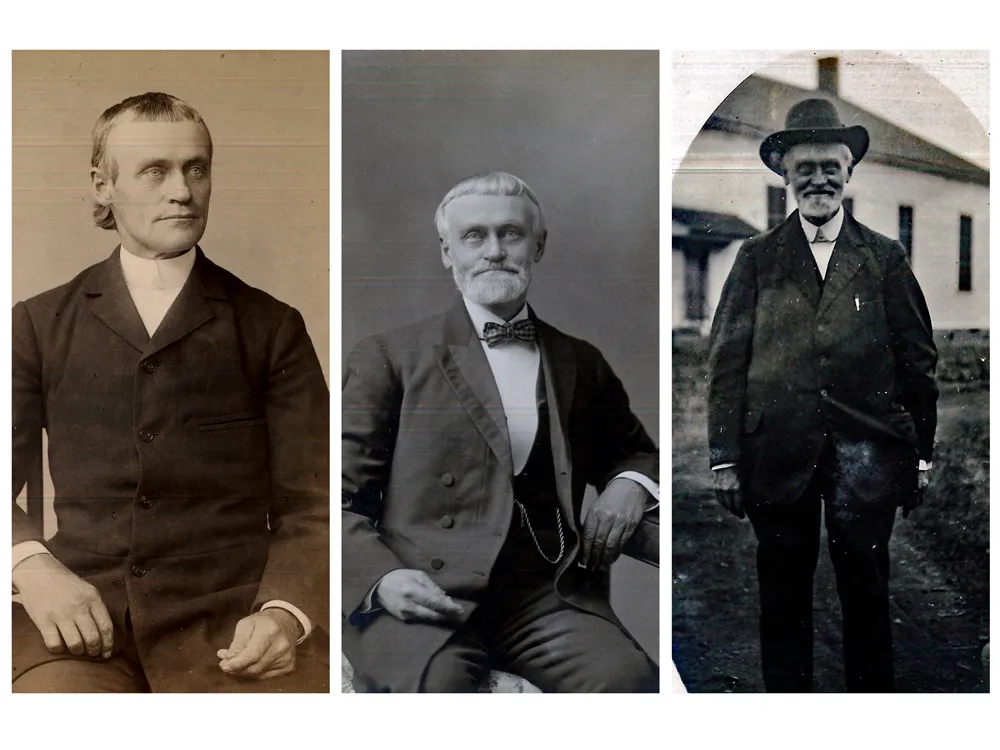

Elder Josiah Barker

1847-1921

Josiah was brought to the Watervliet Shakers when he was less than a year old, yet he frequently visited with his natural family members throughout his life

The journals note his frequent projects requiring mechanical skills. These included fixing the waterworks and clocks, installing glass, and wallpapering rooms.

Brother Josiah was also very active as a singer. He often led singing meetings and instructed the other Shakers in learning new songs. He was among the group of Shakers who performed in Albany in 1870.

In 1886 he was moved from the North Family to the Church Family. He was appointed as Second Elder, assuming the role of postmaster at the same time.

One year later he became the Elder of the Church Family. He seems to have remained in that capacity the rest of his life. He retained ties at the North Family and assisted with administrative matters after the death of Elder Alexander Work in 1909.

As a Trustee, he worked with closely with Eldress Anna Case at the South Family who also served as Trustee for the Watervliet community. As the Shakers declined in number, the West and North Families were closed. Together, they were responsible for overseeing the consolidation and sale of the properties.

The Watervliet Shaker community had to deal with public harassment throughout their history. These included disturbances during worship services, and more serious attacks such as arson.

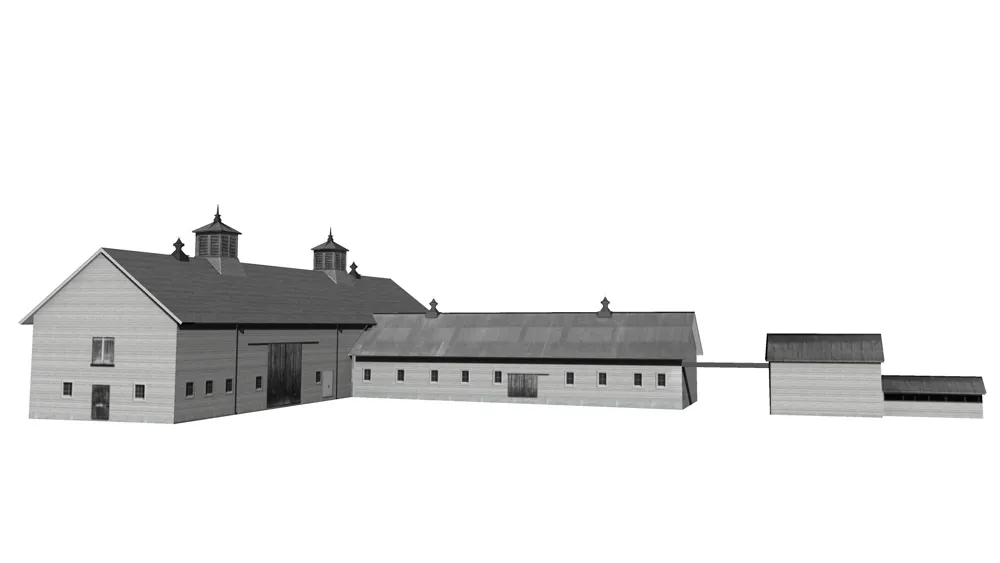

In 1914, the barn complex along what is now Heritage Lane was destroyed by an arsonist's fire. While the Church Family members were few in number, they had faith that God would provide a future for them.

In 1915, Elder Josiah took the insurance money and oversaw the construction of a new complex. This included a hay barn, silo, cow barn, and manure shed. The barn complex reflects the importance of agriculture throughout the history of the Shakers.

For many decades, the Shakers relied on hired labor for farming and other economic activities. When Elder Josiah was ill with a serious case of hiccoughs in 1919, he stayed at the South Family for several weeks. The South Family journal noted that “the [Church Family] hired men (James Tribley, Fred Tribley, Fred Willey, Mr. Baumes) come to see him every day and get their orders.”

Fully recovered one month later, Josiah traveled by train to Cortland to purchase milk cows for the South and Church Families.

Josiah Barker’s death in 1921 signaled the end of the Church Family.

Four years later, only ten years after the barn complex was built, the remaining four Sisters left the community and the Church Family property was sold. The barn’s future was not what the Shakers had hoped for, yet it continues to serve a regional community as a popular site for a variety of events.